I have been thinking about how I can introduce my colleagues in the music history and ethnomusicology worlds to the tools and techniques I have learned in my Digital History coursework. It seems as though the ethos of digital history is one of open access and sharing information, and I think tools like Tropy and QGIS are incredible tools, yet I don’t think as many people in my music-specific fields know about them. Thus, I have been thinking about hosting a workshop on DH tools for music historians. More on that later.

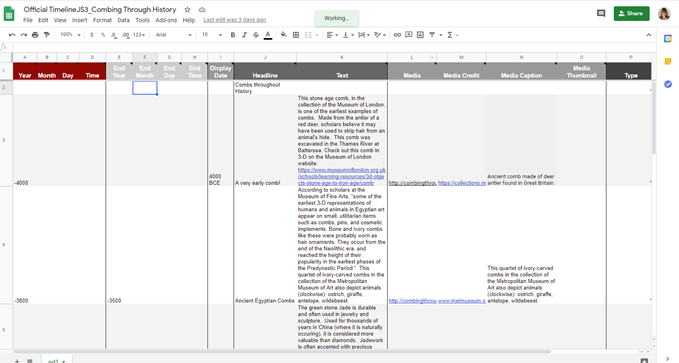

The Knight Lab, out of Northwestern University, has developed many tools for sharing history, including Timeline JS, StoryMaps, StoryLine, and Juxtapose (to name a few). For our Combing Through History DH project, I have created a Timeline JS of combs throughout history, before I knew it was part of this module. It has been a great learning experience figuring it out on my own, and I really think it is one of the most user-friendly interfaces I have learned, thus far. TimelineJS uses a Google Docs template, and has a number of fields for various types of data. I include a screenshot of my timeline information here:

Once completed, you copy the Google Docs URL in your own personal Google Drive, paste it into the Knight Labs website, and voila, a Timeline is born. My timeline is not complete yet, but here is what I have so far, using WordPress’s Knight Timeline plugin:

For my second tutorial, I spent some time with Zooniverse. According to their website,

“The Zooniverse is the world’s largest and most popular platform for people-powered research. This research is made possible by volunteers — more than a million people around the world who come together to assist professional researchers. Our goal is to enable research that would not be possible, or practical, otherwise. Zooniverse research results in new discoveries, datasets useful to the wider research community, and many publications.”

https://www.zooniverse.org/

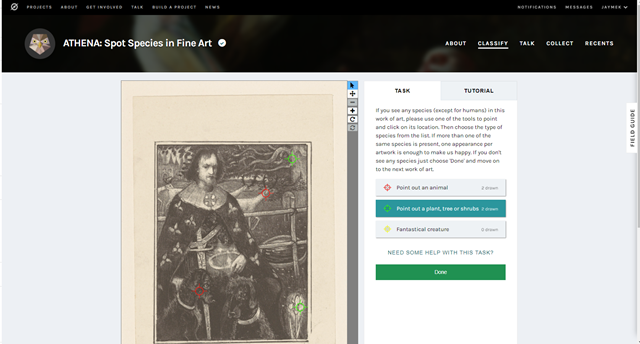

I chose the “Athena: Spot Species in Fine Art” project which is based out of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. The goal is simple: spot the animals, plants, and fantastic creatures in the provided works of art.

As you can see in the image above, the simple interface allows you to click on the animal/plant/creature using their color-coded system, and identify everything you see. By logging into their system, you can be added to the author list for any subsequent publications related to your contributions.

In the past I have participated in wiki-edit-athons and have contributed to Smithsonian public transcription projects. Participating in these projects is an exciting way to feel like you are part of the larger historical community, especially the projects I have helped with that have nothing to do with my own research areas. I have never taught or assigned this kind of crowd sourcing assignment to my students, but I think it could be an interesting experiment. Shannon Kelly cautions:

“A digital writing assignment is not always enough to increase digital literacy; a more pronounced understanding and implementation of digital pedagogy on behalf of the contributing instructor makes the project more effective.”

Shannon Kelley, “Getting on the Map: A Case Study in Digital Pedagogy and Undergraduate Crowdsourcing,” DHQ 11.3 (2017).

Thus, in order to make this kind of assignment worth it, the instructor must be clear about the skills she must train them to do before starting the project, and identify what she wants the students to learn and contribute. Fortunately, new publications like Claire Battershill and Shawna Ross’s 2017 book, Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom: A Practical Introduction for Teachers, Lecturers, and Students give us clear guidance on how to integrate DH into the classroom. Their book is a practical resource for those interested in incorporating DH into their work.